The evolution of Tang Soo Do from Shotokan Karate is a complex story woven through colonialism, cultural preservation, and personal legacy. As someone who has trained in Traditional tang Soo Do, Shotokan, and Chung Do Kwan Tae Kwon Do, I approach this topic with both scholarly respect and firsthand insight. Understanding this transformation isn’t merely academic; it’s essential to grasping the philosophical and technical roots of our Korean martial traditions.

The Historical Backdrop: Korea Under Japanese Rule

From 1910 to 1945, Korea endured a brutal Japanese occupation. During this period, Japan sought to extinguish the Korean history and make them part of Japan. Traditional Korean martial arts—such as Taekkyeon and Subak—were suppressed or lost, while Japanese culture, language, and practices were enforced. One of the most influential imports was Karate, particularly Shotokan, developed by Gichin Funakoshi and rooted in Okinawan and Japanese martial heritage.

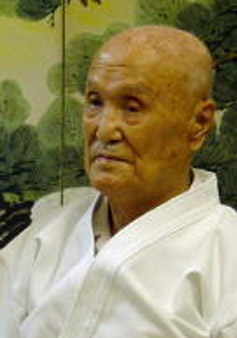

Young Korean men who studied in Japan often encountered Shotokan directly. Among them was Won Kuk Lee, who would later become one of the most pivotal figures in modern Korean martial arts history.

Grandmaster Won Kuk Lee and the Birth of Chung Do Kwan

Won Kuk Lee studied law in Japan and trained in Shotokan under Gichin Funakoshi and his son Gigo Funakoshi. Upon returning to Korea, he sought to introduce what he had learned to a country in cultural recovery after liberation from Japan.

Lee would file a request to open a school with the Japanese Governor General in Korea and an army general, Nobuyuki Abe (son of a samurai), and was denied twice before receiving approval on his third attempt.

In 1944, Lee founded the Chung Do Kwan (“Blue Wave School”), the first recognized Korean martial arts school in the modern era. Lee chose the name “Chung Do Kwan” rather than use Shotokan saying “The son should be named different than the father.”

While he taught what was essentially Shotokan Karate, he did so with Korean terminology, cultural values, and a long-term vision of restoring national identity through martial practice.

Chung Do Kwan became the foundation for Tang Soo Do and what would later evolve into Tae Kwon Do. Many of Lee’s students—such as General Choi Hong Hi (who later founded the ITF) and Hwang Kee (who founded Moo Duk Kwan)—went on to shape Korean martial arts in distinct ways. But all of them, in the early days, practiced techniques nearly indistinguishable from Shotokan.

The Technical Influence of Shotokan

For those who have trained in both systems, the similarities between early Tang Soo Do and Shotokan are unmistakable:

Stances: Deep front stances (zenkutsu dachi) and back stances (kokutsu dachi) appear with identical structure.

Forms (Hyung/Kata): Many hyung in Tang Soo Do are direct adaptations of Shotokan kata, such as Pyong Ahn (Heian) and Bassai (Passai/Bal Sae).

Philosophy: Both arts emphasize discipline, character development, and a linear power-generation method rooted in biomechanical efficiency.

However, over time, Tang Soo Do began to incorporate Korean kicking styles, more dynamic leg techniques, and a distinct aesthetic and cultural identity, differentiating it from its Japanese predecessor.

My Tang Soo Do Lineage and Experience Across Traditions

My own journey reflects this evolution. I trained in Traditional Tang Soo Do, under the tutelage of Master Yun Tak Bong in Chong Dong Ri, South Korea, I immersed myself in Tang Soo Do and it became a huge part of who I am as a person and my life for the past 40 years.

Training in Korea allowed me to feel the Korean heritage, and when I began training in Shotokan three years later, I felt the roots —and harmony—between Japanese and Korean martial traditions. While forms and fundamentals mirrored Shotokan, the cultural approach was uniquely Korean: a greater emphasis on spiritual etiquette, community, and honoring national resilience.

Tang Soo Do as a Cultural Reclamation

While its origins lie in Shotokan, Tang Soo Do represent more than a martial adaptation—it is a cultural reclamation. Korean masters took what was imposed during occupation and, through national pride and innovation, reshaped it into something their own. It’s a powerful reminder that martial arts are never static; they are living systems, continually evolving and formed by history, struggle, and vision.

Conclusion: Honoring Both Roots and Branches

As martial artists, we owe it to ourselves—and our students—to understand where our techniques come from. Tang Soo Do is not merely “like Karate”; it IS Karate, but through men like Won Kuk Lee, and generations of Korean masters, it became something distinct….Korean Karate.

When we bow at the start of class, we don’t just honor our instructor. We bow to a legacy forged in adversity, shaped by cultural determination, and refined through generations. Understanding this story enriches our practice and deepens our respect for the art we carry forward.

Tang Soo!